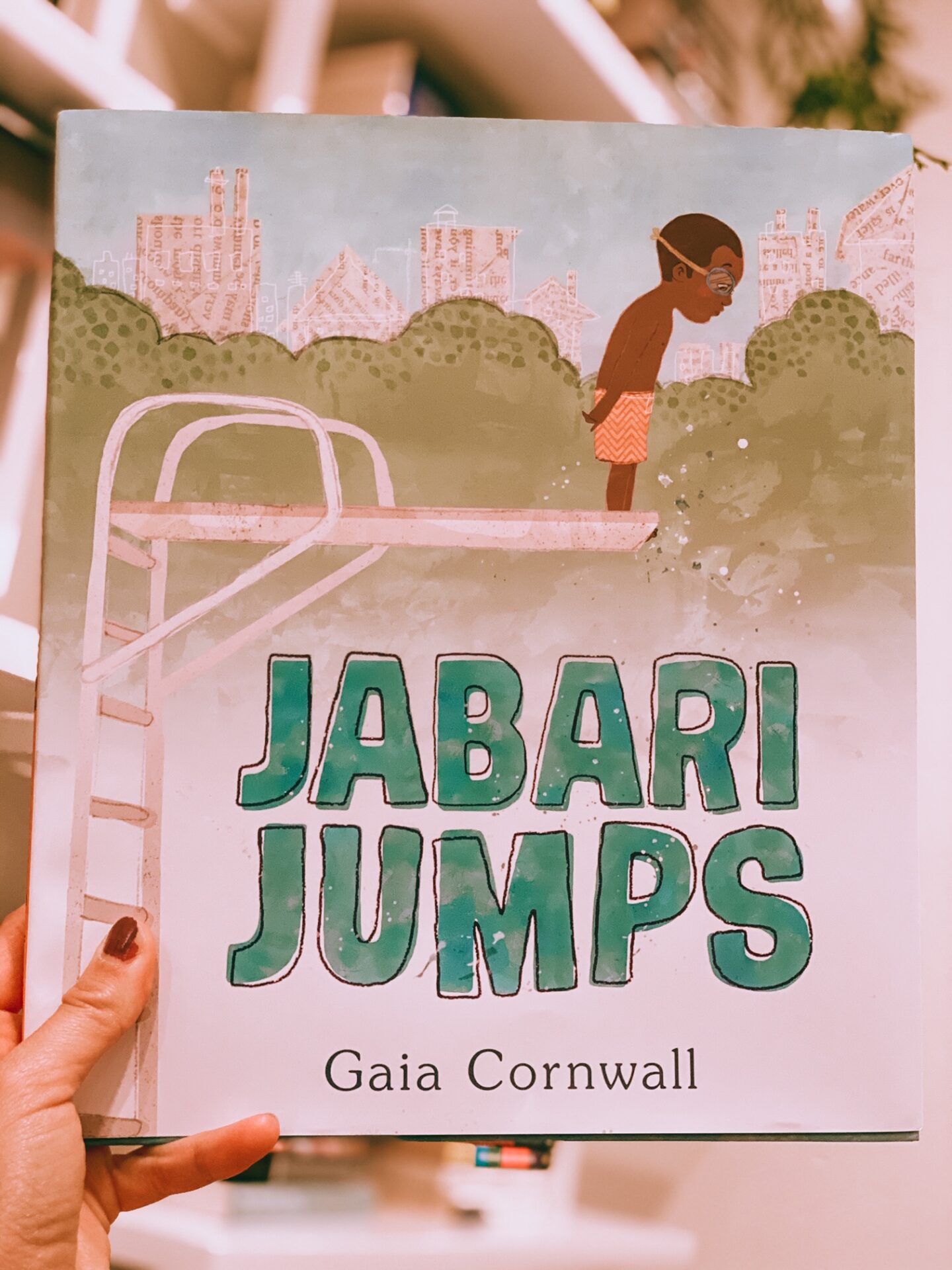

This book is important because it is beautiful, and pure, and well-written. It is also important because Jabari is a little African American boy, going to the pool on a summer day, and doing normal, sweet, everyday little boy things.

This second fact is especially important, especially today.

Jabari Jumps by Gaia Cornwall is about a young boy who is both thrilled and terrified by the prospect of jumping off the diving board (which is playfully depicted in the illustrations as being about 70 feet too high for current safety standards) for the first time.

He gets in line, smiles at his dad, and then does what we all do when we’re sitting at our desks before a big meeting, or phone call, or lunch-date: he finds anything and everything else he can do besides jumping off the diving board.

Eventually, the book ends as it should: with Jabari’s dad teaching him a lesson about the relationship between fear and fun, and Jabari leaping joyfully into the pool.

As a teacher, and a human being, I see a lot of myself and my students in Jabari.

At the beginning of my teaching career, I, a middle class white woman, taught in several different inner-city public schools in Los Angeles. I also traveled to Israel, to teach English to upper-elementary kids in Nazareth.

Sometimes, when I shared anecdotes from these experiences with other, middle class white people in my life, they would ask, “what were the kids like?”

And I would answer, “they were like kids.”

Now I don’t mean to disregard or in any way diminish the unique life experiences of the kids I worked with. Many of the students I taught in Inglewood and Boyle Heights were struggling with, and rising above, situations that I am sure would have defeated me: experiences that were likely instrumental in shaping them into the people they are today. The students I worked with in Israel had to have been defined, at least in some way, by the constant conflict around them. I don’t think it is possible to evacuate from your classroom to a bomb shelter several times a month as a missile siren blares throughout the school hallways and not be changed because of it.

However, the students I taught in Israel were also pretty goofy. A lot of them didn’t want to listen to me, and some talked about me behind my back in Hebrew (I speak very little Hebrew). They ate Cheetos, and peanut-butter sandwiches for lunch, and listened to Pitbull at recess on the yard. My students in LA were also a little goofy. They thought I was pretty “uncool,” and ate Cheetos (with chile and lime) and peanut butter sandwiches at lunch. Many of them also listened to Pitbull at recess on the yard.

Throughout my 10 years of teaching, I have worked with a lot of different kids, from a lot of different backgrounds. Yes, they are all different, but they are also mostly the same.

Most kids are at least a little bit scared to try new things. Most kids want to do well in school, even if they pretend they don’t. Most kids like junk food, and the music their parents tell them not to listen to. Most kids want to have friends, and be accepted by their peers. All kids have parents who would do absolutely anything in the world to keep them safe.

The world today is a weird one. We’re so connected online, but so separate from each other in real life. So many people have forgotten, or maybe never learned, not only that kids are kids, but that people are people, and that, at the end of the day, we all just want to be safe and loved.

If you have a kid, or know a kid, or, hell, even see a kid, buy them Jabari Jumps. Once we start remembering that Jabari’s feelings are just human feelings, maybe we’ll stop spending so much time pushing each other away.

Click to buy: