The summer before sixth grade, I was still pretty hopeful that my letter to Hogwarts was coming in the mail. I knew that my older brother probably wasn’t a wizard, or he would’ve been able to “magic” himself out of all the trouble he got into. My little brother might have been a wizard, but only because he had glasses, and a neighborhood kid had once told him he looked like Harry Potter. If anyone in the family really deserved to be a witch—really had the potential for magic—it was me.

When the first day of sixth grade arrived and I had not, in fact, received a visit from Hagrid, or an owl from Dumbledore, I wouldn’t say I was crushed. In my heart of hearts, I knew that none of it was real. In fact, at that point in time, I had already met J.K. Rowling herself (and yes, I am no longer the fan of hers I once was), and I knew for a fact that she was a mere mortal like myself. I knew that she had created the fantasy land where lonely, forgotten children were suddenly transported into a world of adventure, danger, and heroism, out of the depths of her very human, albeit extraordinary, imagination, and that I was going to have to continue to muddle through muggle school for another 7 years.

Yet in spite of this fact, I had still held on to a shred of hope—even up to that last look back at our mailbox as I hopped in the car. I refused to stop believing because even when we know that something is fake, or a fantasy, or a figment of your own, or someone else’s imagination, the idea of it can still liven up our lives a little bit, and infuse whimsy, wonder and magic into the sometimes mundane business of the everyday.

As I grew up, I didn’t always allow myself to suspend disbelief in this way. By the time I reached high school, I still loved to escape into books, but I also started learning how to mask my sensitivity and insecurity with sarcasm and cynicism. By the time I was an adult, I had practiced myself into a pretty negative outlook on life—always more certain that the worst would happen, than hopeful for the best.

Becoming a parent made me reflect on a lot of things, the most significant of which was my own perspective on the world, and the way I express that to others—both intentionally, and not. When I think of the character traits I want to gift my daughter, cynicism and negativity definitely don’t make list. Instead, I would love to show her that even grown-ups can be happy, hopeful, dreamers, who still believe that their wildest dreams are possible. I would love for my daughter to hold on to her sense of wonder and imagination, and to always see the world as a magical place, even when it tries to prove itself otherwise.

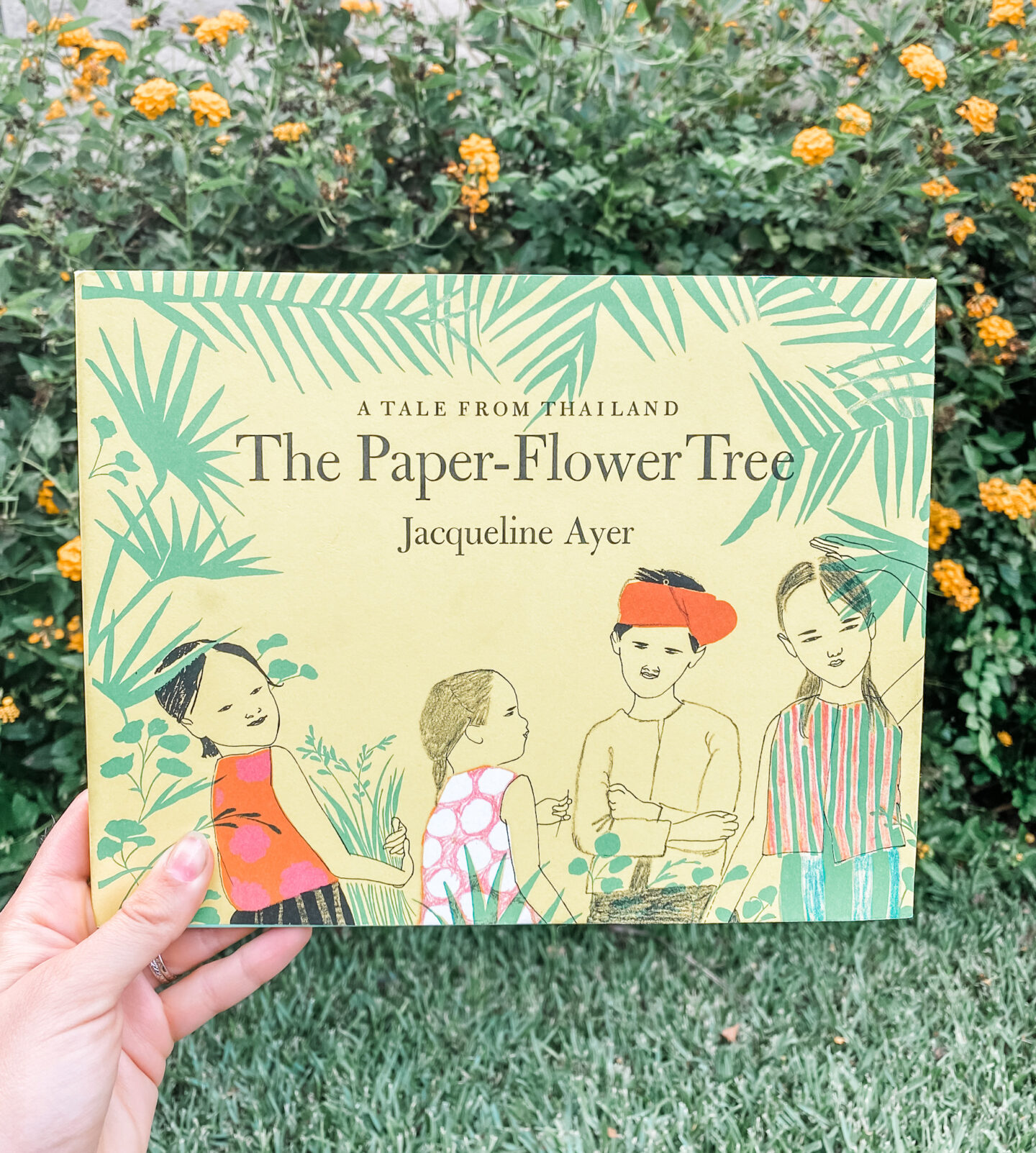

The Paper Flower Tree by Jacqueline Ayer is a story about a girl named Miss Moon who refuses to see the world through anything other than rose-colored glasses. When a travelling caravan of artists, magicians and musicians comes to town, Miss Moon is enthralled by one old man’s “paper flower tree.” The old man offers to sell her a paper flower, but she can’t afford it, so he ends up gifting her one of the smallest flowers—one with a “seed” (or bead) inside that he tells her she can plant. “Plant it,” he says. “and perhaps it will grow. I make no promises. Perhaps it will grow. Perhaps it will not.”

Miss Moon plants the flower and waits all year for it to grow. Her friends and neighbors tell her she is wasting her time—that she was swindled and lied to. But Miss Moon can’t forget how beautiful the paper flower tree was, and she continues to believe. Eventually, the old man returns with his caravan of travelling entertainers, and Miss Moon confronts him about her tree (or lack thereof).

The old man repeats what he had told her before, and Miss Moon heads off, seemingly undeterred, to enjoy the festivities. In the morning, lo and behold, a paper flower tree has grown in her backyard. When Miss Moon’s neighbors once again attempt to convince her that she’s been tricked, Miss Moon continues to ignore them. “The didn’t think her tree was real. She knew it was. She was as happy as a little girl could be.”

Honestly, this book (written for children, of course) blew my mind. So many of us (myself included) ARE those cynical neighbors. When people share their wildest hopes and dreams, and we find them too wild, or weird, or unrealistic, we cut them down, tell them it’s impossible, and perhaps even laugh and their “ignorance” of the way the world really works.

While I may be “right” in taking such a position, reading this book made me wonder: what’s the point in refusing to believe?

Why dwell on the fact that people sometimes want to trick and manipulate us? Or the reality that life tends to be composed of more moments of suffering than sunshine? Or the truth that magic, most likely isn’t real, and we’ll be stuck adhering to the oh-so limiting laws of nature for the rest of our tragically short lives? NO POINT AT ALL, that’s what.

In this story, Miss Moon refuses to give in to the negativity of those around her, or to stop believing in the possibility of magic. The travelling salesman, no doubt, sees this most enviable quality in her, and the strength of her belief inspires him to play into it—to make it “real” for her.

When my daughter was almost three years old, we saw Santa at the mall. She gleefully sat on his lap, asked for an Elsa doll, and told him that yes, Rudolf was her favorite reindeer. When we left, I held her hand, and asked if she enjoyed meeting Santa.

“Yes,” she said, somewhat matter-of-factly, “but he’s just pretend.”

Needless to say, I was shocked. When I reflected on it later, I remembered that we had visited Disneyland about a month prior to meeting Santa, and had spent the day talking about how the “scarier” characters (like Chewbacca and the Queen of Hearts) were “just pretend,” so her application of that truth to the Santa scenario wasn’t too surprising. But it definitely crushed me a little. I remember not really knowing what to say, and definitely not wanting to lie, so I told her the truth: yes, Santa was pretend.

But I also told her that, sometimes, we like to pretend that pretend things are real, because it makes life a little more fun, and exciting and magical. She nodded, and seemed to understand, and asked if I was going to buy her the Elsa doll for Christmas.

This year, Margot seems to be pretty excited for Santa to come. And, if she had any inkling that the woman who played Elsa at her birthday party wasn’t the real Elsa, she never let on. I’m not sure if she remembers our experience at the mall, or if she’s just becoming less literal in her middle-toddlerhood, but either way, I’m happy about it.

Whether we know in our hearts that the magic is real or not doesn’t really matter. It’s when we allow ourselves to believe—even when it’s crazy, or stupid, or a little bit weird—that we can create a more magical world for ourselves, and start really living again, in the possibility-filled reality so many of us left behind in childhood.

So, in short, keep dreaming, and imagining, and stop worrying about what your neighbors think. You’ll be the one with a paper flower tree in the end.

The Book: Click to Purchase